I was a guest panelist yesterday on the al-Jazeera show, The Stream, talking about the promise and perils of transhumanism. I was joined by Robin Hanson of George Mason University and Ari Schulman of the New Atlantis.

A format like this doesn't lend itself to more a nuanced and thoughtful discussion. There's only so much you can say in such a short amount of time, and within the constraints of sound-bites and targeted questions that tend towards sensationalism—and all while trying to keep the conversation as accessible as possible given such a wide and diverse audience. That said, the segment wasn't terrible and I was able to get my two cents in.

March 29, 2012

March 28, 2012

Could human and computer viruses merge?

Via Scientific American:

Although this possibility may sound like a foray into science fiction, information security experts believe the blurring of the boundaries between computer and biological viruses is not so far-fetched—and could have very real consequences.Link.

As TechWorld reports, Axelle Apvrille and Guillaume Lovet of the network security company Fortinet presented a paper comparing human and computer virology and exploring some of the potential dangers at last week’s Black Hat Europe conference.

Both computer and biological viruses, they explain in their paper, can be defined as “information that codes for parasitic behavior.” In biology, a virus’s code is written in DNA or RNA and is much smaller than the code making up a computer virus. The DNA of a flu virus, for example, could be described with about 23,000 bits, whereas the average computer virus would fall in a range 10 to 100 times bigger.

The origins of each virus are strikingly different: A computer virus is designed, whereas a biological virus evolves under pressure from natural selection. But what would happen if these origins are switched? Could hackers code for a super-virus, or a computer virus emerge out of the information “wilderness” and evolve over time?

Apvrille and Lovet argued that both scenarios are possible, with a few caveats to each. Scientists have already synthesized viruses such as polio and SARS for research purposes, so it’s conceivable that someone could synthesize viruses as bioweaponry. That said, Apvrille and Lovet observed that viruses are notoriously difficult to control, and it’s hard to imagine anyone could use a viral weapon without it backfiring.

J. Hughes on democratic transhumanism, personhood, and AI

James Hughes, the executive director of the IEET, was recently interviewed about democratic transhumanism, personhood theory, and AI. He was kind enough to share his responses with me:

Q: You created the term "democratic transhumanism," so how do you define it?

JH: The term "democratic transhumanism" distinguishes a biopolitical stance that combines socially liberal or libertarian views (advocating internationalist, secular, free speech, and individual freedom values), with economically egalitarian views (pro-regulation, pro-redistribution, pro-social welfare values), with an openness to the transhuman benefits that science and technology can provide, such as longer lives and expanded abilities. It was an attempt to distinguish the views of most transhumanists, who lean Left, from the minority of highly visible Silicon Valley-centered libertarian transhumanists, on the one hand, and from the Left bioconservatives on the other.

In the last six or seven years the phrase has been supplanted by the descriptor "technoprogressive" which is used to describe the same basic set of Enlightenment values and policy proposals:

In Enlightenment thought "persons" are beings aware of themselves with interests that they enact over time through conscious life plans. Personhood is a threshold which confers some rights, while there are levels of rights both above and below personhood. Society is not obliged to treat beings without personhood, such as most animals, human embryos and humans who are permanently unconscious, as having a fundamental right to exist in themselves, a "right to life." To the extent that non-persons can experience pain however we are obliged to minimize their pain. Above personhood we oblige humans to pass thresholds of age, training and testing, and licensure before they can exercise other rights, such as driving a car, owning a weapon, or prescribing medicine. Children have basic personhood rights, but full adult persons who have custody over them have an obligation to protect and nurture children to their fullest possible possession of mature personhood rights.

Who to include in the sphere of persons is a matter of debate, but at the IEET we generally believe that apes and cetaceans meet the threshold. Beyond higher mammals however, the sphere of potential kinds of minds is enormous, and it is very likely that some enhanced animals, post-humans and machine minds will possess only a sub-set of the traits that we consider necessary for conferring personhood status. For instance a creature might possess a high level of cognition and communication, but no sense of self-awareness or separate egoistic interests. In fact, when designing AI we will probably attempt to avoid creating creatures with interests separate from our own, since they could be quite dangerous. Post-humans meanwhile may experiment with cognitive capacities in ways that sometimes take them outside of the sphere of "persons" with political claims to rights, such as if they suppress capacities for empathy, memory or identity.

Q: What ethical obligations are involved in the development of A.I.?

We first have an ethical obligation to all present and future persons to ensure that the creation of machine intelligence enhances their life options, and doesn't diminish or extinguish them. The most extreme version of this dilemma is posed by the possibility of a hostile superintelligence which could be an existential risk to life as we understand it. Short of that the simple expansion of automation and robotics will likely eliminate most forms of human labor, which could result in widespread poverty, starvation and death, and the return of a feudal order. Conversely a well-regulated transition to an automated future with a basic income guarantee could create an egalitarian society in which humans all benefit from leisure.

We also have ethical obligations in relationship to the specific kinds of AI will create. As I mentioned above, we should avoid creating self-willed machine minds because of the dangers they might pose to the humans they are intended to serve. But we also have an obligation to the machine minds themselves to avoid making them self-aware. Our ability to design self-aware creatures with desires that could be thwarted by slavery, or perhaps even worse to design creatures who only desire to serve humans and have no will to self-development, is very troubling. If self-willed self-aware machine minds do get created, or emerge naturally, and are not a catastrophic threat, then we have an obligation to determine which ones can fit into the social order as rights-bearing citizens.

Q: What direction do you see technology headed - robots as tools or robots as beings?

It partly depends on whether self-aware machine minds are first created by brain-machine interfaces, brain emulation and brain "uploading," or are designed de novo in machines, or worse, emerge spontaneously. The closer the connection to human brains that machine minds have the more likely they are to retain the characteristics of personhood that we can recognize and work with as fellow citizens. But a mind that emerges more from silicon is unlikely to have anything in common with human minds, and more likely to either be a tool without a will of its own, or a being that we can't communicate or co-exist with.

Q: You created the term "democratic transhumanism," so how do you define it?

JH: The term "democratic transhumanism" distinguishes a biopolitical stance that combines socially liberal or libertarian views (advocating internationalist, secular, free speech, and individual freedom values), with economically egalitarian views (pro-regulation, pro-redistribution, pro-social welfare values), with an openness to the transhuman benefits that science and technology can provide, such as longer lives and expanded abilities. It was an attempt to distinguish the views of most transhumanists, who lean Left, from the minority of highly visible Silicon Valley-centered libertarian transhumanists, on the one hand, and from the Left bioconservatives on the other.

In the last six or seven years the phrase has been supplanted by the descriptor "technoprogressive" which is used to describe the same basic set of Enlightenment values and policy proposals:

Q: In simple terms, what is the "personhood theory? " How do you think it is/will be applied to A.I.?Human enhancement technologies, especially anti-aging therapies, should be a priority of publicly financed basic research, be well regulated for safety, and be included in programs of universal health care

Structural unemployment resulting from automation and globalization needs to be ameliorated by a defense of the social safety net, and the creation of universal basic income guarantees

Global catastrophic risks, both natural and man-made, require new global programs of research, regulation and preparedness

Legal and political protections need to be expanded to include all self-aware persons, including the great apes, cetaceans, enhanced animals and humans, machine minds, and hybrids of animals, humans and machines

Alliances need to be built between technoprogressives and other progressive movements around sustainable development, global peace and security, and civil and political rights, on the principle that access to safe enabling technologies are fundamental to a better future

In Enlightenment thought "persons" are beings aware of themselves with interests that they enact over time through conscious life plans. Personhood is a threshold which confers some rights, while there are levels of rights both above and below personhood. Society is not obliged to treat beings without personhood, such as most animals, human embryos and humans who are permanently unconscious, as having a fundamental right to exist in themselves, a "right to life." To the extent that non-persons can experience pain however we are obliged to minimize their pain. Above personhood we oblige humans to pass thresholds of age, training and testing, and licensure before they can exercise other rights, such as driving a car, owning a weapon, or prescribing medicine. Children have basic personhood rights, but full adult persons who have custody over them have an obligation to protect and nurture children to their fullest possible possession of mature personhood rights.

Who to include in the sphere of persons is a matter of debate, but at the IEET we generally believe that apes and cetaceans meet the threshold. Beyond higher mammals however, the sphere of potential kinds of minds is enormous, and it is very likely that some enhanced animals, post-humans and machine minds will possess only a sub-set of the traits that we consider necessary for conferring personhood status. For instance a creature might possess a high level of cognition and communication, but no sense of self-awareness or separate egoistic interests. In fact, when designing AI we will probably attempt to avoid creating creatures with interests separate from our own, since they could be quite dangerous. Post-humans meanwhile may experiment with cognitive capacities in ways that sometimes take them outside of the sphere of "persons" with political claims to rights, such as if they suppress capacities for empathy, memory or identity.

Q: What ethical obligations are involved in the development of A.I.?

We first have an ethical obligation to all present and future persons to ensure that the creation of machine intelligence enhances their life options, and doesn't diminish or extinguish them. The most extreme version of this dilemma is posed by the possibility of a hostile superintelligence which could be an existential risk to life as we understand it. Short of that the simple expansion of automation and robotics will likely eliminate most forms of human labor, which could result in widespread poverty, starvation and death, and the return of a feudal order. Conversely a well-regulated transition to an automated future with a basic income guarantee could create an egalitarian society in which humans all benefit from leisure.

We also have ethical obligations in relationship to the specific kinds of AI will create. As I mentioned above, we should avoid creating self-willed machine minds because of the dangers they might pose to the humans they are intended to serve. But we also have an obligation to the machine minds themselves to avoid making them self-aware. Our ability to design self-aware creatures with desires that could be thwarted by slavery, or perhaps even worse to design creatures who only desire to serve humans and have no will to self-development, is very troubling. If self-willed self-aware machine minds do get created, or emerge naturally, and are not a catastrophic threat, then we have an obligation to determine which ones can fit into the social order as rights-bearing citizens.

Q: What direction do you see technology headed - robots as tools or robots as beings?

It partly depends on whether self-aware machine minds are first created by brain-machine interfaces, brain emulation and brain "uploading," or are designed de novo in machines, or worse, emerge spontaneously. The closer the connection to human brains that machine minds have the more likely they are to retain the characteristics of personhood that we can recognize and work with as fellow citizens. But a mind that emerges more from silicon is unlikely to have anything in common with human minds, and more likely to either be a tool without a will of its own, or a being that we can't communicate or co-exist with.

March 26, 2012

Sentient Developments Podcast: Episode 2012.03.26

Sentient Developments Podcast for the week of March 26, 2012.

Topics for this week's episode: How to build a Dyson sphere in five (relatively) easy steps, how to take over the Galaxy with self-replicating probes, the Fermi Paradox, and the Simulation Argument.

Tracks used in this episode:

Topics for this week's episode: How to build a Dyson sphere in five (relatively) easy steps, how to take over the Galaxy with self-replicating probes, the Fermi Paradox, and the Simulation Argument.

Tracks used in this episode:

- Beach House: "Myth"

- Keep Shelly in Athens: "Our Own Dream"

- Rose Cousins: "One Way"

March 25, 2012

Sentient Developments Podcast Episode Archive

Take a look at the sidebar in the Sentient Developments Podcast section. I've added a page that links to every podcast I've ever done (2006 to 2012). The page an also be found here.

March 20, 2012

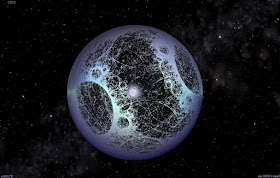

How to build a Dyson sphere in five (relatively) easy steps

Let's build a Dyson sphere!

And why wouldn't we want to?

By enveloping the sun with a massive array of solar panels, humanity would graduate to a Type 2 Kardashev civilization capable of utilizing nearly 100% of the sun's energy output. A Dyson sphere would provide us with more energy than we would ever know what to do with while dramatically increasing our living space. Given that our resources here on Earth are starting to dwindle, and combined with the problem of increasing demand for more energy and living space, this would seem to a good long-term plan for our species.

Implausible you say? Something for our distant descendants to consider?

Think again: We are closer to being able to build a Dyson Sphere than we think. In fact, we could conceivably get going on the project in about 25 to 50 years, with completion of the first phase requiring only a few decades. Yes, really.

Now, before I tell you how we could do such a thing, it's worth doing a quick review of what is meant by a "Dyson sphere".

Dyson Spheres, Swarms, and Bubbles

The Dyson sphere, also referred to as a Dyson shell, is the brainchild of the physicist and astronomer Freeman Dyson. In 1959 he put out a two page paper titled, "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation" in which he described a way for an advanced civilization to utilize all of the energy radiated by their sun. This hypothetical megastructure, as envisaged by Dyson, would be the size of a planetary orbit and consist of a shell of solar collectors (or habitats) around the star. With this model, all (or at least a significant amount) of the energy would hit a receiving surface where it can be used. He speculated that such structures would be the logical consequence of the long-term survival and escalating energy needs of a technological civilization.

Needless to say, the amount of energy that could be extracted in this way is mind-boggling. According to Anders Sandberg, an expert on exploratory engineering, a Dyson sphere in our solar system with a radius of one AU would have a surface area of at least 2.72x1017 km2, which is around 600 million times the surface area of the Earth. The sun has an energy output of around 4x1026 W, of which most would be available to do useful work.

I should note at this point that a Dyson sphere may not be what you think it is. Science fiction often portrays it as a solid shell enclosing the sun, usually with an inhabitable surface on the inside. Such a structure would be a physical impossibility as the tensile strength would be far too immense and it would be susceptible to severe drift.

Dyson's original proposal simply assumed there would be enough solar collectors around the sun to absorb the starlight, not that they would form a continuous shell. Rather, the shell would consist of independently orbiting structures, around a million kilometres thick and containing more than 1x105 objects. Consequently, a "Dyson sphere" could consist of solar captors in any number of possible configurations. In a Dyson swarm model, there would be a myriad of solar panels situated in various orbits. It's generally agreed that this would be the best approach. Another plausible idea is that of the Dyson bubble in which solar sails, as well as solar panels, would be put into place and balanced by gravity and the solar wind pushing against it.

For the purposes of this discussion, I'm going to propose that we build a Dyson swarm (sometimes referred to as a type I Dyson sphere), which will consist of a large number of independent constructs orbiting in a dense formation around the sun. The advantage of this approach is that such a structure could be built incrementally. Moreover, various forms of wireless energy transfer could be used to transmit energy between its components and the Earth.

Megascale construction

So, how would we go about the largest construction project ever undertaken by humanity?

As noted, a Dyson swarm can be built gradually. And in fact, this is the approach we should take. The primary challenges of this approach, however, is that we will need advanced materials (which we still do not possess, but will likely develop in the coming decades thanks to nanotechnology), and autonomous robots to mine for materials and build the panels in space.

Now, assuming that we will be able to overcome these challenges in the next half-decade or so—which is not too implausible— how could we start the construction of a Dyson sphere?

Oxford University physicist Stuart Armstrong has devised a rather ingenious and startling simple plan for doing so—one which he claims is almost within humanity's collective skill-set. Armstrong's plan sees five primary stages of construction, which when used in a cyclical manner, would result in increasingly efficient, and even exponentially growing, construction rates such that the entire project could be completed within a few decades.

Broken down into five basic steps, the construction cycle looks like this:

And yes, you read that right: we're going to have to mine materials from Mercury. Actually, we'll likely have to take the whole planet apart. The Dyson sphere will require a horrendous amount of material—so much so, in fact, that, should we want to completely envelope the sun, we are going to have to disassemble not just Mercury, but Venus, some of the outer planets, and any nearby asteroids as well.

Why Mercury first? According to Armstrong, we need a convenient source of material close to the sun. Moreover, it has a good base of elements for our needs. Mercury has a mass of 3.3x1023 kg. Slightly more than half of its mass is usable, namely iron and oxygen, which can be used as a reasonable construction material (i.e. hematite). So, the useful mass of Mercury is 1.7x1023 kg, which, once mined, transported into space, and converted into solar captors, would create a total surface area of 245g/m2. This Phase 1 swarm would be placed in orbit around Mercury and would provide a reasonable amount of reflective surface area for energy extraction.

There are five fundamental, but fairly conservative, assumptions that Armstrong relies upon for this plan. First, he assumes it will take ten years to process and position the extracted material. Second, that 51.9% of Mercury's mass is in fact usable. Third, that there will be 1/10 efficiency for moving material off planet (with the remainder going into breaking chemical bonds and mining). Fourth, that we'll get about 1/3 efficiency out of the solar panels. And lastly, that the first section of the Dyson sphere will consist of a modest 1 km2 surface area.

And here's where it gets interesting: Construction efficiency will at this point start to improve at an exponential rate.

Consequently, Armstrong suggests that we break the project down into what he calls "ten year surges." Basically, we should take the first ten years to build the first array, and then, using the energy from that initial swarm, fuel the rest of the project. Using such a schema, Mercury could be completely dismantled in about four ten-year cycles. In other words, we could create a Dyson swarm that consists of more than half of the mass of Mercury in forty years! And should we wish to continue, if would only take about a year to disassemble Venus.

And assuming we go all the way and envelope the entire sun, we would eventually have access to 3.8x1026 Watts of energy.

Dysonian existence

Once Phase 1 construction is complete (i.e. the Mercury phase), we could use this energy for other purposes, like megascale supercomputing, building mass drivers for interstellar exploration, or for continuing to build and maintain the Dyson sphere.

Interestingly, Armstrong would seem to suggest that this might be enough energy to serve us. But other thinkers, like Sandberg, suggest that we should keep going. But in order for us to do so we would have to deconstruct more planets. Sandberg contends that both the inner and outer solar system contains enough usable material for various forms of Dyson spheres with a complete 1 AU radius (which would be around 42 kg/m2 of the sphere). Clearly, should we wish to truly attain Kardashev II status, this would be the way to go.

And why go all the way? Well, it's very possible that our appetite for computational power will become quite insatiable. It's hard to predict what a post-Singularity or post-biological civilization would do with so much computation power. Some ideas include ancestor simulations, or even creating virtual universes within universes. In addition, an advanced civilization may simply want to create as many positive individual experiences as possible (a kind of utilitarian imperative). Regardless, digital existence appears to be in our future, so computation will eventually become our most valuable and sought after resource.

That said, whether we build a small array or one that envelopes the entire sun, it seems clear that the idea of constructing a Dyson sphere should no longer be relegated to science fiction or our dreams of the deep future. Like other speculative projects, like the space elevator or terraforming Mars, we should seriously consider putting this alongside our other near-term plans for space exploration and work.

And given the progressively worsening condition of Earth and our ever-growing demand for living space and resources, we may have no other choice.

And why wouldn't we want to?

By enveloping the sun with a massive array of solar panels, humanity would graduate to a Type 2 Kardashev civilization capable of utilizing nearly 100% of the sun's energy output. A Dyson sphere would provide us with more energy than we would ever know what to do with while dramatically increasing our living space. Given that our resources here on Earth are starting to dwindle, and combined with the problem of increasing demand for more energy and living space, this would seem to a good long-term plan for our species.

Implausible you say? Something for our distant descendants to consider?

Think again: We are closer to being able to build a Dyson Sphere than we think. In fact, we could conceivably get going on the project in about 25 to 50 years, with completion of the first phase requiring only a few decades. Yes, really.

Now, before I tell you how we could do such a thing, it's worth doing a quick review of what is meant by a "Dyson sphere".

Dyson Spheres, Swarms, and Bubbles

The Dyson sphere, also referred to as a Dyson shell, is the brainchild of the physicist and astronomer Freeman Dyson. In 1959 he put out a two page paper titled, "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation" in which he described a way for an advanced civilization to utilize all of the energy radiated by their sun. This hypothetical megastructure, as envisaged by Dyson, would be the size of a planetary orbit and consist of a shell of solar collectors (or habitats) around the star. With this model, all (or at least a significant amount) of the energy would hit a receiving surface where it can be used. He speculated that such structures would be the logical consequence of the long-term survival and escalating energy needs of a technological civilization.

Needless to say, the amount of energy that could be extracted in this way is mind-boggling. According to Anders Sandberg, an expert on exploratory engineering, a Dyson sphere in our solar system with a radius of one AU would have a surface area of at least 2.72x1017 km2, which is around 600 million times the surface area of the Earth. The sun has an energy output of around 4x1026 W, of which most would be available to do useful work.

I should note at this point that a Dyson sphere may not be what you think it is. Science fiction often portrays it as a solid shell enclosing the sun, usually with an inhabitable surface on the inside. Such a structure would be a physical impossibility as the tensile strength would be far too immense and it would be susceptible to severe drift.

Dyson's original proposal simply assumed there would be enough solar collectors around the sun to absorb the starlight, not that they would form a continuous shell. Rather, the shell would consist of independently orbiting structures, around a million kilometres thick and containing more than 1x105 objects. Consequently, a "Dyson sphere" could consist of solar captors in any number of possible configurations. In a Dyson swarm model, there would be a myriad of solar panels situated in various orbits. It's generally agreed that this would be the best approach. Another plausible idea is that of the Dyson bubble in which solar sails, as well as solar panels, would be put into place and balanced by gravity and the solar wind pushing against it.

For the purposes of this discussion, I'm going to propose that we build a Dyson swarm (sometimes referred to as a type I Dyson sphere), which will consist of a large number of independent constructs orbiting in a dense formation around the sun. The advantage of this approach is that such a structure could be built incrementally. Moreover, various forms of wireless energy transfer could be used to transmit energy between its components and the Earth.

Megascale construction

So, how would we go about the largest construction project ever undertaken by humanity?

As noted, a Dyson swarm can be built gradually. And in fact, this is the approach we should take. The primary challenges of this approach, however, is that we will need advanced materials (which we still do not possess, but will likely develop in the coming decades thanks to nanotechnology), and autonomous robots to mine for materials and build the panels in space.

Now, assuming that we will be able to overcome these challenges in the next half-decade or so—which is not too implausible— how could we start the construction of a Dyson sphere?

Oxford University physicist Stuart Armstrong has devised a rather ingenious and startling simple plan for doing so—one which he claims is almost within humanity's collective skill-set. Armstrong's plan sees five primary stages of construction, which when used in a cyclical manner, would result in increasingly efficient, and even exponentially growing, construction rates such that the entire project could be completed within a few decades.

Broken down into five basic steps, the construction cycle looks like this:

- Get energy

- Mine Mercury

- Get materials into orbit

- Make solar collectors

- Extract energy

And yes, you read that right: we're going to have to mine materials from Mercury. Actually, we'll likely have to take the whole planet apart. The Dyson sphere will require a horrendous amount of material—so much so, in fact, that, should we want to completely envelope the sun, we are going to have to disassemble not just Mercury, but Venus, some of the outer planets, and any nearby asteroids as well.

Why Mercury first? According to Armstrong, we need a convenient source of material close to the sun. Moreover, it has a good base of elements for our needs. Mercury has a mass of 3.3x1023 kg. Slightly more than half of its mass is usable, namely iron and oxygen, which can be used as a reasonable construction material (i.e. hematite). So, the useful mass of Mercury is 1.7x1023 kg, which, once mined, transported into space, and converted into solar captors, would create a total surface area of 245g/m2. This Phase 1 swarm would be placed in orbit around Mercury and would provide a reasonable amount of reflective surface area for energy extraction.

There are five fundamental, but fairly conservative, assumptions that Armstrong relies upon for this plan. First, he assumes it will take ten years to process and position the extracted material. Second, that 51.9% of Mercury's mass is in fact usable. Third, that there will be 1/10 efficiency for moving material off planet (with the remainder going into breaking chemical bonds and mining). Fourth, that we'll get about 1/3 efficiency out of the solar panels. And lastly, that the first section of the Dyson sphere will consist of a modest 1 km2 surface area.

And here's where it gets interesting: Construction efficiency will at this point start to improve at an exponential rate.

Consequently, Armstrong suggests that we break the project down into what he calls "ten year surges." Basically, we should take the first ten years to build the first array, and then, using the energy from that initial swarm, fuel the rest of the project. Using such a schema, Mercury could be completely dismantled in about four ten-year cycles. In other words, we could create a Dyson swarm that consists of more than half of the mass of Mercury in forty years! And should we wish to continue, if would only take about a year to disassemble Venus.

And assuming we go all the way and envelope the entire sun, we would eventually have access to 3.8x1026 Watts of energy.

Dysonian existence

Once Phase 1 construction is complete (i.e. the Mercury phase), we could use this energy for other purposes, like megascale supercomputing, building mass drivers for interstellar exploration, or for continuing to build and maintain the Dyson sphere.

Interestingly, Armstrong would seem to suggest that this might be enough energy to serve us. But other thinkers, like Sandberg, suggest that we should keep going. But in order for us to do so we would have to deconstruct more planets. Sandberg contends that both the inner and outer solar system contains enough usable material for various forms of Dyson spheres with a complete 1 AU radius (which would be around 42 kg/m2 of the sphere). Clearly, should we wish to truly attain Kardashev II status, this would be the way to go.

And why go all the way? Well, it's very possible that our appetite for computational power will become quite insatiable. It's hard to predict what a post-Singularity or post-biological civilization would do with so much computation power. Some ideas include ancestor simulations, or even creating virtual universes within universes. In addition, an advanced civilization may simply want to create as many positive individual experiences as possible (a kind of utilitarian imperative). Regardless, digital existence appears to be in our future, so computation will eventually become our most valuable and sought after resource.

That said, whether we build a small array or one that envelopes the entire sun, it seems clear that the idea of constructing a Dyson sphere should no longer be relegated to science fiction or our dreams of the deep future. Like other speculative projects, like the space elevator or terraforming Mars, we should seriously consider putting this alongside our other near-term plans for space exploration and work.

And given the progressively worsening condition of Earth and our ever-growing demand for living space and resources, we may have no other choice.

March 19, 2012

Sentient Developments Podcast: Episode 2012.03.19

Sentient Developments Podcast for the week of March 19, 2012.

Topics for this week's episode: Raising IQ with creatine and Double N-Back Training, the red meat scare, the Ashley Treatment five years later, destroying asteroids with nukes, re-engineering humans to deal with climate change, the Fermi Paradox, and the ongoing perils to democracy.

Tracks used in this episode:

Topics for this week's episode: Raising IQ with creatine and Double N-Back Training, the red meat scare, the Ashley Treatment five years later, destroying asteroids with nukes, re-engineering humans to deal with climate change, the Fermi Paradox, and the ongoing perils to democracy.

Tracks used in this episode:

- Soft Metals: "The Cold World Waits"

- The Knife: "Marble House"

- Zed's Dead: "Pyramid Song" (remix)

- Evy Jane: "Sayso"

March 17, 2012

Making artificial limbs beautiful and personalized

Prosthetics can’t replicate the look and feel of lost limbs, argues industrial designer Scott Summit, but they can carry a lot of personality. At TEDxCambridge, he shows 3D-printed, individually designed prosthetic legs that are unabashedly artificial and completely personal.

The talk features a fantastic quote from Summit that could also apply to us "normal functioning" humans looking ahead to a transhuman future:

The talk features a fantastic quote from Summit that could also apply to us "normal functioning" humans looking ahead to a transhuman future:

If you're designing for the person—for a real person—you don't settle for the minimum functional requirements. You see how far beyond that you can go where the rewards really are way out in the fringe of how far past that document you can go. And if you can nail that, you stand to improve the quality of life for somebody for every moment for the rest of their life.

TED: Questions no one knows the answers to

There's a new TED-Ed series that tackles questions that we don't know the answer to. In this first episode, TED Curator Chris Anderson asks: How many universes are there? And Why can't we see evidence of alien life? On the latter question, his answers are somewhat pedestrian and even outlandish, but Anderson takes a wide swath at the possibilities and includes some genuine solutions, including the Great Filter and postbiological existence.

The Red Scare: Paleo bloggers destroy the Harvard anti-meat study

By now I'm sure you've come across the red-meat-will-kill-you meme in some form or another. The hysteria was triggered by a Harvard School of Public Health study which indicated that, "Red meat consumption is associated with an increased risk of total, CVD [cardiovascular disease], and cancer mortality."

Thankfully, a number of Paleo bloggers and nutritionists have taken the time to pick the study apart and reveal its flaws:

Thankfully, a number of Paleo bloggers and nutritionists have taken the time to pick the study apart and reveal its flaws:

- Red Meat & Mortality & the Usual Bad Science: Zoë Harcombe

- Will Eating Red Meat Kill You?: Mark's Daily Apple

- Red Meat Consumption and Mortality: Caveman Doctor

- Red Meat Study: Here We Go Again: Constantly Varied

- Red Meat: Part of a Healthy Diet?: Robb Wolf

- Nutrition data was collected via Food Frequency Questionnaires. Yes, folks just had to remember what they thought they ate.

- Confounders galore. The higher meat consumption group tended to be overweight, smoked and was less active. Apparently they did not get a Paleo cohort in that mix?

- Correlation does not equal causation.

Dave Asprey: Creatine + Dual N-Back training will boost IQ

Dave Asprey, the Bulletproof Executive, claims that his IQ was raised 30 points by taking creatine and going through Dual N-Back training exercises. While I'm suspicious of the 30 point claim (seriously?!), I'm quite sure there's some merit to his proposition that the combination of the two can be a very potent cognitive booster. I myself have written about the merits of creatine and N-Back training in the past, though I haven't tried the latter. Perhaps it's time I did.

The "Ashley Treatment" five years later

Five years after the advent of the Ashley Treatment, Peter Singer chimes in and provides a review of the procedure which now impacts the lives of over a hundred severely disabled children:

Today, Ashley is 14. Her mental condition has not changed, but her size and weight have remained that of a nine-year-old. Her father remains convinced that he and his wife made the right decision for Ashley, and that the treatment made her more likely to be comfortable, healthy and happy. He describes her as "completely loved" and her life "as good as we can possibly make it". There seem to be no grounds for holding the opinion that the treatment was not in Ashley's best interests.It's worth noting that my article, Helping Families Care for the Helpless, was the first published defense of the Ashley Treatment.

As for the claim that it was unnatural, well, in one sense all medical treatment is unnatural; it enables us to live longer, and in better health, than we naturally would. Perhaps the most "natural" thing for Ashley's parents to do with their severely disabled daughter would have been to abandon her to the wolves and vultures, as parents have done with such children for most of human existence. Fortunately, we have evolved beyond such "natural" practices, which are abhorrent to civilised people. The issue of treating Ashley with dignity was never, in my view, a genuine one. Infants are adorable, but not dignified, and the same is true of older and larger human beings who remain at the mental level of an infant. You don't acquire dignity just by being born a member of the species Homo sapiens.

What of the slippery slope argument? The Guardian has found 12 families that have used the "Ashley treatment" and believes more than 100 children may have been administered with hormones to keep them small. The fact that a few other families are using the treatment, however, does not show there has been any descent down a slope. Take the cases of "Tom" and "Erica," two other severely intellectually disabled children who have been given similar treatment to Ashley. Their mothers are convinced that the treatment has enabled their children to live happier lives, and are grateful to Ashley's father for being open about how they are coping with Ashley's disability.

March 16, 2012

Sandberg et al clarify claim that we should 'bioengineer humans to tackle climate change'

Oh, man. Lots of transhumanists in the news these days making quite a stir. First it was Julian Savulescu having to defend his decision to include a paper about infanticide in the Journal of Medical Ethics, and now Anders Sandberg is under the gun for his claim that we should bioengineer humans to tackle climate change. Here's the rundown from The Guardian:

Earlier this week, The Atlantic ran an eye-catching, disturbing interview with a professor of philosophy and bioethics at New York University called S. Matthew Liao. He was invited to discuss a forthcoming paper he has co-authored which will soon be published in the journal Ethics, Policy & Environment.Anders Sandberg is among the paper's authors (which also includes Dr Rebecca Roache), and he has provided some clarification on the matter:

But within just a few hours of the interview going live a torrent of outrage and abuse was being directed towards him online. As I tweeted at the time, the interview was indeed "unsettling". Liao explained how his paper – entitled, "Human Engineering and Climate Change" – explored the so-far-ignored subject of how "biomedical modifications of humans" could be used to "mitigate and/or adapt to climate change". The modifications discussed included: giving people drugs to make them have an adverse reaction to eating meat; making humans smaller via gene imprinting and "preimplantation genetic diagnosis"; lowering birth-rates through "cognitive enhancement"; genetically engineering eyesight to work better in the dark to help reduce the need for lighting; and the "pharmacological enhancement of altruism and empathy" to engender a better "correlation" with environmental problems.

Both the interview and the paper itself include a prominent disclaimer. As the paper says:

To be clear, we shall not argue that human engineering ought to be adopted; such a claim would require far more exposition and argument than we have space for here. Our central aim here is to show that human engineering deserves consideration alongside other solutions in the debate about how to solve the problem of climate change. Also, as we envisage it, human engineering would be a voluntary activity – possibly supported by incentives such as tax breaks or sponsored health care – rather than a coerced, mandatory activity.

However, that wasn't enough to prevent an extremely hostile reception to such ideas. Climate sceptics were the first to vent their anger. Somewhat inevitability, terms such as "eugenics", "Nazis" and "eco fascists" were quickly being bandied around. One sceptic blogger said that the "sick" Liao and his co-authors should be "kept in Guantanamo". Another said the paper "presages the death of science, and indeed the death of reason, in the West".

Most reactions are not based on what we actually wrote. People who comment on anything online have usually not read it, and then people comment on them, and so on. You are lucky if people remember the original topic, let alone any argument.There's lots more from Anders and Roache.

People seem to assume we are some kind of totalitarian climate doomsters who advocate biotechnological control over people. What we are actually saying is that changing our biology might be part of solving environmental problems, and that some changes might not just be permissible but work well with a liberal ethics.

Climate change and many other problems have upstream and downstream solutions. For example, 1) human consumption leads to 2) a demand for production and energy, which leads to 3) industry, which leads to 4) greenhouse gas emissions, which lead to 5) planetary heating, which leads to 6) bad consequences. One solution might be to try to consume less (fix 2). We can also make less emissive industry (fix the 3-4 link), remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere (reduce 4), geoengineering that cools the planet (reduce 5) or adapt to a changed world (handle 6). Typically people complain about the downstream solutions like geoengineering that they are risky or don't actually solve the cause of the problem, and say we should go for upstream solutions (where a small shift affects the rest of the chain). So, what would be the most upstream solution? Change human desires or consumption. While this can be done partially by persuasion and culture, there are many strong evolved drivers in human nature that act against it. But we can also affect the drivers.

For example, making people smarter is likely to make them better at solving environmental problems, caring about the environment, adopting a more long-term stance, cooperate better and have fewer children. It is of course desirable for a long list of other reasons too, and many people would freely choose to use enhancements to achieve this even if they cared little about the world. If there was a modification that removed the desire for meat, it would likely have not just green effects but also benefit health and animal welfare - again many might decide to go for it, with no external compulsion.

Nonhuman Personhood Rights (and Wrongs)

Via Eric Michael Johnson of Scientific American:

This is not as radical an idea as it may sound. The law is fully capable of making and unmaking “persons” in the strictly legal sense. For example, one Supreme Court case in 1894 (Lockwood, Ex Parte 154 U.S. 116) decided that it was up to the states “to determine whether the word ‘person’ as therein used [in the statute] is confined to males, and whether women are admitted to practice law in that commonwealth.” As atrocious as this ruling sounds, such a precedent continued well into the twentieth century and, in 1931, a Massachusetts judge ruled that women could be denied eligibility to jury status because the word “person” was a term that could be interpreted by the court.Not sure I agree with the whole "artificial persons" concept. That's a half-assed approach to the matter that's both scientifically and politically unsatisfying. Either you're a person or you aren't. Corporations aren't persons. Cetaceans, great apes, and elephants most certainly are.

Such a flexible interpretation of personhood was demonstrated most dramatically in 1886 when the Supreme Court granted personhood status to the first nonhuman. In this case it was a corporation and Southern Pacific Railroad (part of robber baron Leland Stanford’s empire) snuck in through a legal loophole to gain full personhood rights under the 14th Amendment. Such rights have now been extended to all corporations under the Citizens United ruling in 2010, which is what allowed Mitt Romney to confidently declare “corporations are people, my friends.”

But prior to 1886, dating back to the 1600s, corporations were viewed as “artificial persons,” a legal turn of phrase that offered certain rights to the companies but without the full rights of citizens. By using the wording of the 14th Amendment (intended to protect former slaves from a state government seeking to “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”) it was ruled that corporations should enjoy the same status. As a result, between 1890 and 1920, out of all the 14th Amendment cases that came before the Supreme Court, 19 dealt with African-Americans while 288 dealt with corporations. With the legal stroke of a pen, artificial persons were granted all the protections of citizens.

But that would be unlikely to happen with whales, dolphins, or even great apes. A “nonhuman person” would have a definition similar to this earlier tradition of “artificial person,” one that grants limited rights that a government is obligated to protect. Furthermore, according to White, the term would only apply under very specific criteria for nonhumans that had self-awareness, complex social as well as emotional lives, and evidence of conscious awareness (so, for example, ants would never be considered persons under law). According to White, these criteria have been met in the case of dolphins and whales and our legal institutions should incorporate this evidence into American jurisprudence.

“One of the most important aspects of science is that scientific progress regularly raises important ethical questions,” said White. “As scientific research produces a more accurate picture of the universe, it often reveals ways that human attitudes and behavior may be out of synch with these new facts.”

Neuroscience and philosophy must work together

March 12, 2012

Sentient Developments Podcast: Episode 2012.03.12

Sentient Developments Podcast for the week of March 12, 2012.

Topics for this week's episode include the perils of Active SETI, the possibility of downloading something nasty from ET, why virtually everyone is wrong about alien threats, Nick Bostrom's claim that we are underestimating existential risks, and the 'create the future' myth.

Tracks used in this episode:

Topics for this week's episode include the perils of Active SETI, the possibility of downloading something nasty from ET, why virtually everyone is wrong about alien threats, Nick Bostrom's claim that we are underestimating existential risks, and the 'create the future' myth.

Tracks used in this episode:

- School of Seven Bells: "Lafaye"

- Long Distance Calling: "Into the Black Wide Open"

- Ulrich Schnauss: "Made of Sky"

March 8, 2012

Nick Bostrom: We're underestimating the risk of human extinction

There's an excellent interview of Nick Bostrom over at The Atlantic in which he argues that humanity is underestimating the risk of human extinction. I highly encourage you to read the entire interview, but here's a quick highlight:

In considering the long-term development of humanity, do you put much stock in specific schemes like the Kardashev Scale, which plots the advancement of a civilization according to its ability to harness energy, specifically the energy of its planet, its star, and then finally the galaxy? Might there be more to human flourishing than just increasing mastery of energy sources?

Bostrom: Certainly there would be more to human flourishing. In fact I don't even think that particular scale is very useful. There is a discontinuity between the stage where we are now, where we are harnessing a lot of the energy resources of our home planet, and a stage where we can harness the energy of some increasing fraction of the universe like a galaxy. There is no particular reason to think that we might reach some intermediate stage where we would harness the energy of one star like our sun. By the time we can do that I suspect we'll be able to engage in large-scale space colonization, to spread into the galaxy and then beyond, so I don't think harnessing the single star is a relevant step on the ladder.

If I wanted some sort of scheme that laid out the stages of civilization, the period before machine super intelligence and the period after super machine intelligence would be a more relevant dichotomy. When you look at what's valuable or interesting in examining these stages, it's going to be what is done with these future resources and technologies, as opposed to their structure. It's possible that the long-term future of humanity, if things go well, would from the outside look very simple. You might have Earth at the center, and then you might have a growing sphere of technological infrastructure that expands in all directions at some significant fraction of the speed of light, occupying larger and larger volumes of the universe---first in our galaxy, and then beyond as far as is physically possible. And then all that ever happens is just this continued increase in the spherical volume of matter colonized by human descendants, a growing bubble of infrastructure. Everything would then depend on what was happening inside this infrastructure, what kinds of lives people were being led there, what kinds of experiences people were having. You couldn't infer that from the large-scale structure, so you'd have to sort of zoom in and see what kind of information processing occurred within this infrastructure.

It's hard to know what that might look like, because our human experience might be just a small little crumb of what's possible. If you think of all the different modes of being, different kinds of feeling and experiencing, different ways of thinking and relating, it might be that human nature constrains us to a very narrow little corner of the space of possible modes of being. If we think of the space of possible modes of being as a large cathedral, then humanity in its current stage might be like a little cowering infant sitting in the corner of that cathedral having only the most limited sense of what is possible.

March 7, 2012

March 6, 2012

March 5, 2012

Sentient Developments Podcast: Episode 2012.03.05

Sentient Developments Podcast for the week of March 5, 2012.

Topics for this week's episode include the Turing Test, artificial consciousness, and machine ethics; Avi Rubin's recent TED Talk on our increasingly hackable world; nootropics, cognitive liberty and limits to the biolibertarian impulse.

Tracks used in this episode:

Topics for this week's episode include the Turing Test, artificial consciousness, and machine ethics; Avi Rubin's recent TED Talk on our increasingly hackable world; nootropics, cognitive liberty and limits to the biolibertarian impulse.

Tracks used in this episode:

- Frankie Rose: "Interstellar"

- Pallbearer: "Foreigner"

- Teengirl Fantasy: "Cheaters"

March 2, 2012

My appearance on The Future and You podcast

I was recently interviewed by Stephen Euin Cobb for his excellent The Future and You Podcast. We spoke for nearly three hours, so he broke the interview down into three separate episodes. He's published the first two, which you can find here and here. Part three will be posted sometime next week.

Topics discussed in the first episode: The importance of studying history in order to extrapolate the future; how democratic transhumanism differs from other flavours of transhumanism; why I am a "technogaian environmentalist" and how that relates to Bright Green Environmentalism; the abolition of suffering in all species; political problems of putting a thermostat on the earth; as well as the good and bad of living an engineered blissful existence permanently.

Topics discussed in the second episode: Is it wise to use our emotions (especially repugnance) as a guide to truth? Giving protective rights to intelligent animals (apes, whales, dolphins, and elephants), and eventually (when the time is right) to artificially intelligent software; augmenting animals to raise their IQ (animal uplifting); the new movie Planet of the Apes; the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey; better ways to conduct the search for extraterrestrials (SETI); Dyson Spheres; the Fermi Paradox; why Stephen Euin Cobb hopes we will forever move to universes of ever increasing dimensionality; as well as artificially created universes and simulated universes.

I'll let you know when the third episode is posted.

Topics discussed in the first episode: The importance of studying history in order to extrapolate the future; how democratic transhumanism differs from other flavours of transhumanism; why I am a "technogaian environmentalist" and how that relates to Bright Green Environmentalism; the abolition of suffering in all species; political problems of putting a thermostat on the earth; as well as the good and bad of living an engineered blissful existence permanently.

Topics discussed in the second episode: Is it wise to use our emotions (especially repugnance) as a guide to truth? Giving protective rights to intelligent animals (apes, whales, dolphins, and elephants), and eventually (when the time is right) to artificially intelligent software; augmenting animals to raise their IQ (animal uplifting); the new movie Planet of the Apes; the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey; better ways to conduct the search for extraterrestrials (SETI); Dyson Spheres; the Fermi Paradox; why Stephen Euin Cobb hopes we will forever move to universes of ever increasing dimensionality; as well as artificially created universes and simulated universes.

I'll let you know when the third episode is posted.

March 1, 2012

Guardian: Eight questions science must answer about consciousness

Anil Seth:"The brain mechanisms of consciousness are being unravelled at a startling pace, with researchers focusing on eight key areas":

Details here.

- What are the critical brain regions for consciousness?

- What are the mechanisms of general anaesthesia?

- What is the self?

- What determines experiences of volition and 'will'?

- What is the function of consciousness? What are experiences for?

- How rich is consciousness?

- Are other animals conscious?

- Are vegetative patients conscious?

Details here.

Avi Rubin on our increasingly hackable world #TED

Pretty scary stuff, particularly for us future cyborgs.

When the Turing Test is not enough: Towards a functionalist determination of consciousness and the advent of an authentic machine ethics

Overview

Empirical research that works to map those characteristics requisite for the identification of conscious awareness are proving increasingly insufficient, particularly as neuroscientists further refine functionalist models of cognition. To say that an agent "appears" to have awareness or intelligence is inadequate. Rather, what is required is the discovery and understanding of those processes in the brain that are responsible for capacities such as sentience, empathy and emotion. Subsequently, the shift to a neurobiological basis for identifying subjective agency will have implications for those hoping to develop self-aware artificial intelligence and brain emulations. The Turing Test alone cannot identify machine consciousness; instead, computer scientists will need to work off the functionalist model and be mindful of those processes that produce awareness. Because the potential to do harm is significant, an effective and accountable machine ethics needs to be considered. Ultimately, it is our responsibility to develop a rigorous understanding of consciousness so that we may identify and work with it once it emerges.

Machine Ethics

Machine consciousness is a neglected area. It's a field related to artificial intelligence and cognitive robotics, but its aim is to define and model those factors required to synthesize consciousness. Neuroscience hypothesizes that consciousness is generated by the interoperation of various parts of the brain, called the neural correlates of consciousness or NCC. Proponents of artificial consciousness (AC) believe computers can emulate this interoperation, which is not yet fully understood. Recent work by Steven Ericsson-Zenith suggests that something is missing from these approaches and a new mechanics is needed to explain consciousness and the behavior of neurons.

Machine ethics as a subfield is even further behind. Because we're having a hard time getting our head around the AI versus AC problem, not too many people are thinking about the ethical and moral issues involved. We need to think about this preemptively. Failure to set standards and guidelines in advance could result in not just serious harm to nascent machine minds, but a dangerous precedent that will become more difficult to overturn as time passes. This will require a multi-disciplinal approach that will combine neuroscience, philosophy, ethics and law.

It's worth noting that machine ethics is a separate issue from robot ethics. The ethics surrounding the actions of autonomous (but mindless) robotic drones and other devices that are controlled remotely is separate issue—and one that will not be discussed here—but it's an important topic nonetheless.

The Problem

There are a number of reasons why machine ethics is being neglected, even if it is a speculative field at this point.

For example, there is the persistence of vitalism. Thinkers like Roger Penrose argue that consciousness studies somehow resides outside of known or even knowable science. While the Vital Force concept has been largely ignored in biology since the times of Harvey, Darwin and Pasteur, it still lingers in some forms in psychology and neuroscience.

Instead, we need to pay more attention to the work of Allan Turing, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts who posited computational and cybernetic models of brain function. It is no coincidence that mind and consciousness studies never really took off with any kind of fervor or sophistication until the advent of computer science. We finally have a model that helps explain cognition. AI theorists have finally been able to study things like patttern recognition, learning, problem solving, theorem proving, game-playing, just to mention only a few.

Another part of the problem is the presence of scientific ignorance, defeatism and denial. Some skeptics claim that machines will never be able to think, that self-awareness and introspection is a biological function. Some even suggest that it's a purely human thing. It's quite possible, therefore, that many AI theorists don't even recognize this as a moral issue.

There is also the fixation on AI. It is important to distinguish AI from AC; artificial intelligence is differentiated from artificial consciousness in that subjective agency is not necessarily present in AI. And by virtue of the absence of subjectivity and sentience, so too goes moral consideration. It is through the instantiation of consciousness that agency truly exists, and by consequence, moral worth.

Another particularly pernicious problem is the impact of human exceptionalism and substrate chauvinism on the topic. Traditionally, the law has divided entities into two categories: persons or property. In the past, individuals (e.g. women, slaves, children) were considered mere property. Law is evolving (through legislation and court decisions) to recognize that individuals are persons; the law is still evolving and will increasingly recognize the states or categories in between.

Extending personhood designation to those entities outside of the human sphere is a pertinent issue for animal rights activists as well as transhumanists. Given our poor track record of denying highly sapient animals such consideration, this doesn't bode well for the future of artificially conscious agents.

As personhood advocates attest, not all persons are humans. A number of nonhuman animals deserve personhood consideration, namely all great apes, cetaceans, elephants, and possibly encephalopds and some birds like the grey parrot. Consequently, these animals cannot be considered mere property. What we're made out of and how we got here doesn't matter. There is no mysterious essence or spirit about humanity that should prevent us from recognizing the moral worth of not just other persons, but of any self-aware, conscious agent.

There's also the issue of empiricism and how it conflicts with true scientific understanding. The Turing Test as a measure of consciousness is problematic. It's an approach that's purely based on behavioral assessments. It only tests how the subject acts and responds. The problem is that this could be simulated intelligence. It also conflates intelligence with consciousness (as already established, intelligence and consciousness are two different things).

The Turing Test also inadequately assesses intelligence. Some human behavior is unintelligent (e.g. random, unpredictable, chaotic, inconsistent, and irrational behavior). Moreover, some intelligent behavior is characteristically non-human in nature, but that doesn't make it unintelligent or a sign of lack of subjective awareness.

It's also subject to the anthropomorphic fallacy. Humans are particularly prone to projecting minds where there aren't.

Lastly, the Turing test fails to account for the difficulty in articulating conscious awareness. There are a number of conscious experiences that we, as conscious agents, have difficulty articulating, yet we experience them nonetheless. For example:

Just because it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck doesn't mean it's a duck. Moreover, just because you've determined that it is a duck doesn't mean you know how the duck works. As Richard Feynman once said, "What I cannot create I cannot understand."

This is why we need to build the duck.

Ethical Implications

There are a number of ethical implications that will emerge once conscious agency is synthesized in a machine. The moment is coming when a piece of software or source code will cease to be an object of inquiry and instead transform into a subject that deserves moral consideration. It's through AI/AC experimentation that we will eventually have to deal with emergent subjective agency in the computer lab—and we'll need to be ready.

There's also the issue of human augmentation. Pending technologies, like synthetic neurons and neural interface devices, will result in brains that are more artificial than biological. We'll need to respect the moral worth of hybridized persons. For example, there's the potential for embedded mechanical implants. The military has envisioned microscanners and biofluidic chips to enable the unobtrusive assessment and remote sensing of a soldier's medical condition. And the health care industry has been investigating nanoscale insulin pumps that will measure blood glucose and release appropriate amounts of insulin to control blood sugar. We are slowly becoming cyborgs.

The advent of whole brain emulation and/or uploads will further the need for a coherent machine ethics. Emulating the brain's functionality will likely be accomplished through the use of synthetic analogues. While the functionalist aspects will largely remain the same, the components themselves will likely be non-biological. Thus, there's a very real potential for substrate chauvinism to take root.

A properly thought-out and articulated machine ethics with supportive legislation will help in maintaining social cohesion and justice. There are longstanding implications given the potential for (post)human speciation and the onset of machine minds. We need to expand the moral and legal circle to include not just all persons (human or otherwise) but any agent with the capacity for subjective awareness.

Solutions

The first thing that needs to happen as we head down this path is to accept cognitive functionalism as a methodological approach.

In recent years we've learned much more about the complexity of the brain. It now appears that perhaps fully half of our entire genetic endowment is involved in constructing the nervous system. The brain has more parts than the skeletomuscular system, which has hundreds of functional parts. This would suggest that the brain is nothing like a single large-scale neural net. Indeed, a quick examination of the index of a book on neuroanatomy will reveal the names of several hundred different organs of the brain.

But brains are one thing. Minds are another. It's clear, however, that minds are what brains do. So, instead of the "looks like a duck" approach, we need to adopt the "proof is in the pudding" approach. To move forward, then, we need to identify and then develop the NCCs sufficient for bringing about subjective awareness in AI. In other words, we need to parse and map out the organs of conscious function.

Fortunately, this work has begun. For example, there's the work of Bernard Baars and his organs of conscious function:

There's also the work of Igor Aleksander:

There have even been attempts to map personhood-specific cognitive function. Take Joseph Fletcher's criteria for example:

Again, we need to identify the sufficient functions responsible for the emergence of self-awareness and by consequence a morally valuable agent. Following that, we can both create and recognizing those functions in a synthesized context, namely AC.

Law

Once the primae facie evidence exists for the presence of a machine mind, we can then head to the courts and make the case for legal protections, and in some advanced cases, machine personhood. The intention will be to use the laws to protect artificial minds.

Essentially, we will need to endow basic fundamental rights as they accorded to any person. It will be important for us to properly assess when the rights of an autonomous system emerges—the exact moment when a piece of code or emulated chunk of brain ceases to be property and is instead an object of moral worth.

As part of the process, we'll need to establish the do's and don'ts. As I see it, qualifying artificial intellects will need to be endowed with the following rights and protections:

These rights will also be accompanied by those protections and freedoms afforded to any person or citizen.

That said, some advanced artificial intellects will need to take part in the social contract. In other words, they will be held accountable for their actions. As it stands, some nonhuman persons (i.e. dolphins and elephants) are not expected to understand and abide by human/state laws (in the same way we don't expect children and the severely disabled to follow laws). Similarly, more basic machine minds will be absolved from civil responsibility (but not their owners or developers).

There's no question, however, that more advanced machine minds with certain endowments will be held accountable for their actions. Consequently, they, along with their developers, will have to be respectful of the law and go about their behavioral programming in a pro-social way. If I may paraphrase Rousseau, in order for some machine minds to participate in the social contract, they will have to be programmed to be free.

In terms of immediate next steps, we need to:

To conclude, it's important to note that one of the most important steps in the process of building a legitimate machine ethics is the recognition of non-animal personhood. Once that happens we can work towards the establishment of legally binding rights that protect animals. In turn, that will set an important precedent for when machine consciousness emerges.

Empirical research that works to map those characteristics requisite for the identification of conscious awareness are proving increasingly insufficient, particularly as neuroscientists further refine functionalist models of cognition. To say that an agent "appears" to have awareness or intelligence is inadequate. Rather, what is required is the discovery and understanding of those processes in the brain that are responsible for capacities such as sentience, empathy and emotion. Subsequently, the shift to a neurobiological basis for identifying subjective agency will have implications for those hoping to develop self-aware artificial intelligence and brain emulations. The Turing Test alone cannot identify machine consciousness; instead, computer scientists will need to work off the functionalist model and be mindful of those processes that produce awareness. Because the potential to do harm is significant, an effective and accountable machine ethics needs to be considered. Ultimately, it is our responsibility to develop a rigorous understanding of consciousness so that we may identify and work with it once it emerges.

Machine Ethics

Machine consciousness is a neglected area. It's a field related to artificial intelligence and cognitive robotics, but its aim is to define and model those factors required to synthesize consciousness. Neuroscience hypothesizes that consciousness is generated by the interoperation of various parts of the brain, called the neural correlates of consciousness or NCC. Proponents of artificial consciousness (AC) believe computers can emulate this interoperation, which is not yet fully understood. Recent work by Steven Ericsson-Zenith suggests that something is missing from these approaches and a new mechanics is needed to explain consciousness and the behavior of neurons.

Machine ethics as a subfield is even further behind. Because we're having a hard time getting our head around the AI versus AC problem, not too many people are thinking about the ethical and moral issues involved. We need to think about this preemptively. Failure to set standards and guidelines in advance could result in not just serious harm to nascent machine minds, but a dangerous precedent that will become more difficult to overturn as time passes. This will require a multi-disciplinal approach that will combine neuroscience, philosophy, ethics and law.

It's worth noting that machine ethics is a separate issue from robot ethics. The ethics surrounding the actions of autonomous (but mindless) robotic drones and other devices that are controlled remotely is separate issue—and one that will not be discussed here—but it's an important topic nonetheless.

The Problem

There are a number of reasons why machine ethics is being neglected, even if it is a speculative field at this point.

For example, there is the persistence of vitalism. Thinkers like Roger Penrose argue that consciousness studies somehow resides outside of known or even knowable science. While the Vital Force concept has been largely ignored in biology since the times of Harvey, Darwin and Pasteur, it still lingers in some forms in psychology and neuroscience.

Instead, we need to pay more attention to the work of Allan Turing, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts who posited computational and cybernetic models of brain function. It is no coincidence that mind and consciousness studies never really took off with any kind of fervor or sophistication until the advent of computer science. We finally have a model that helps explain cognition. AI theorists have finally been able to study things like patttern recognition, learning, problem solving, theorem proving, game-playing, just to mention only a few.

Another part of the problem is the presence of scientific ignorance, defeatism and denial. Some skeptics claim that machines will never be able to think, that self-awareness and introspection is a biological function. Some even suggest that it's a purely human thing. It's quite possible, therefore, that many AI theorists don't even recognize this as a moral issue.

There is also the fixation on AI. It is important to distinguish AI from AC; artificial intelligence is differentiated from artificial consciousness in that subjective agency is not necessarily present in AI. And by virtue of the absence of subjectivity and sentience, so too goes moral consideration. It is through the instantiation of consciousness that agency truly exists, and by consequence, moral worth.

Another particularly pernicious problem is the impact of human exceptionalism and substrate chauvinism on the topic. Traditionally, the law has divided entities into two categories: persons or property. In the past, individuals (e.g. women, slaves, children) were considered mere property. Law is evolving (through legislation and court decisions) to recognize that individuals are persons; the law is still evolving and will increasingly recognize the states or categories in between.

Extending personhood designation to those entities outside of the human sphere is a pertinent issue for animal rights activists as well as transhumanists. Given our poor track record of denying highly sapient animals such consideration, this doesn't bode well for the future of artificially conscious agents.

As personhood advocates attest, not all persons are humans. A number of nonhuman animals deserve personhood consideration, namely all great apes, cetaceans, elephants, and possibly encephalopds and some birds like the grey parrot. Consequently, these animals cannot be considered mere property. What we're made out of and how we got here doesn't matter. There is no mysterious essence or spirit about humanity that should prevent us from recognizing the moral worth of not just other persons, but of any self-aware, conscious agent.

There's also the issue of empiricism and how it conflicts with true scientific understanding. The Turing Test as a measure of consciousness is problematic. It's an approach that's purely based on behavioral assessments. It only tests how the subject acts and responds. The problem is that this could be simulated intelligence. It also conflates intelligence with consciousness (as already established, intelligence and consciousness are two different things).

The Turing Test also inadequately assesses intelligence. Some human behavior is unintelligent (e.g. random, unpredictable, chaotic, inconsistent, and irrational behavior). Moreover, some intelligent behavior is characteristically non-human in nature, but that doesn't make it unintelligent or a sign of lack of subjective awareness.

It's also subject to the anthropomorphic fallacy. Humans are particularly prone to projecting minds where there aren't.

Lastly, the Turing test fails to account for the difficulty in articulating conscious awareness. There are a number of conscious experiences that we, as conscious agents, have difficulty articulating, yet we experience them nonetheless. For example:

- How do you know how to move your arm?

- How do you choose which words to say?

- How do you locate your memories?

- How do you recognize what you see?

- Why does seeing feel different from Hearing?

- Why are emotions so hard to describe?

- Why does red look so different from green?

- What does "meaning" mean?

- How does reasoning work?

- How does commonsense reasoning work?

- How do we make generalizations?

- How do we get (make) new ideas?

- Why do we like pleasure more than pain?

- What are pain and pleasure, anyway?

Just because it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck doesn't mean it's a duck. Moreover, just because you've determined that it is a duck doesn't mean you know how the duck works. As Richard Feynman once said, "What I cannot create I cannot understand."

This is why we need to build the duck.

Ethical Implications