_____

[Warning: this review contains lots of spoilers, but please, don't let that stop you.]

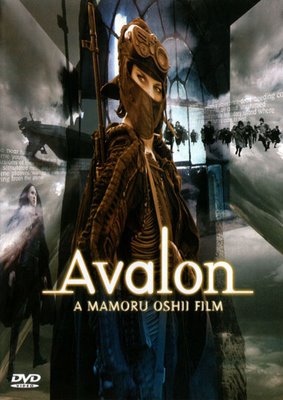

[Warning: this review contains lots of spoilers, but please, don't let that stop you.]Back in 2001, Japanese anime director Mamoru Oshii went to Poland to direct his first live action movie, Avalon. Oshii, who is primarily known for his work in anime, is the director of the acclaimed 90's science fiction classic, Ghost in the Shell (1995) and the sequel, Ghost in the Shell II: Innocence (2004).

Now, before I get too deep into this review, I just want to make it clear that from a production perspective Avalon is a borderline B movie. The film was created on a limited budget and lacks the polished look and crisp dialogue of most mainstream films, particularly those that come out of Hollywood. The look and feel of Avalon is similar to a made-for-TV movie, although many of the special effects are of a superior quality. Also, the movie was a Japanese-Polish collaboration, which, given its Orwellian setting, gives it a unique authenticity.

That being said, like Ghost in the Shell, Avalon offers considerable food for thought.

Avalon is set in the near future, a world in which fully immersive virtual reality gaming is all the rage. Many players are able to earn a living through gaming, particularly in an ultra-violent war game called 'Avalon'. The game, however, is highly addictive and dangerous, causing some less skilled players to suffer from severe and permanent brain damage. Those who meet this fate are referred to as the 'unreturned.' Because of the risks, the game is outlawed by the state and made illegal.

The main character, Ash, lives a boring, lonely and mundane life in the real world. Her life in the simulation, by contrast, is filled with action, danger, and fulfillment. Where her real life is repetitive, pointless and safe, her virtual life is dynamic, challenging and frightening. Avalon is a world in which people come to value their virtual lives over their real ones. The game-master himself is looked upon in near reverential terms and is unmistakably made to resemble a priest.

In the game itself, Ash is an elite player driven to complete level after level. Her motivation for doing so is not entirely clear, even to her, save for the hope that something greater awaits her in the 'next level.' Eventually, after the introduction of a rival player and the discovery of certain clues, Ash succeeds at finding an elusive hidden level.

As Ash transitions to the mysterious level, the sepia tones that dominated the film's appearance are washed away to reveal a full colour panorama. The sensation is much like in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy opens the door in her black and white world and enters a new world filled with dazzling colour. Where Dorothy enters a world of fantasy and whimsy, Ash finds herself undergoing an existential paradigm shift.

Ash's previous reality, one that was draped in drab monotone, is immediately understood to represent a partially realized existence. The overwhelming sepia and lack of colour come to symbolize limitations to human and social capacity – limits of perception, cognition and sensation. Alternately, the new world, with all its visual richness and dynamism, opens up an entirely new set of possibilities for Ash.

Oshii is making a number of interesting analogies here, including a comparison of the past with the future. But more aptly, he is comparing life as it was in communist Europe to modern life in capitalist democracies. It is no accident that Oshii made this movie in Poland using native actors and Polish dialogue.

Prior to her entry into the final level, Ash's world was filled with Orwellian imagery. Bleak and eerie tones dominated the screen along with retro-futurist gadgetry reminiscent of such films as 1984, Brazil and Gattaca. Computer terminals were limited to 3D text displays. Books containing no text whatsoever filled shelves. People gathered at communal soup kitchens to eat gruel. Public transportation was dominated by shaky old-fashioned streetcars. The new world, by contrast – Ash's mysterious new level - was filled with billboards, streets filled with bustling people, modern cars and a rich cultural life (including a vivid performance by an actual orchestra).

The new level, however, also presented its challenges. Ash was instructed to hunt down a 'computer bug' -- a former player who escaped to the advanced level. The 'bug' turns out to be a former teammate of Ash's, Murphy, and when she finally confronts him he declares, “Reality is what we tell ourselves it is!” As instructed, she shoots the defector and transcends to yet another level -- another mode of existence -- but this time to the mythical Avalon itself.

In Oshii's Avalon, the comparison of a totalitarian system with that of a modern democratic one can be understood as a transition of simulations in the postmodernist sense. It is reminiscent of Baudrillard's cultural simulation as constructed by the media and the state itself.

Similarly, according to modal reality theory, any system that appears rational to an observer will be construed as real; what we as observers don't know, however, is what possibilities might lie beyond our own modal reality. In the Avalon war game, by advancing to the final level, Ash is given an opportunity to transcend her original modal reality and enter into one with entirely new possibilities.

The relevancy to transhumanism is also pertinant. Given the potential human augmentation, and given the possibility of our own existential mode shift (i.e. the Singularity and virtual existences), humanity might find itself much like Dorothy and Ash, exiting a world of black and white and entering a world of undiscovered colour.

Ultimately, Avalon is a treatise on how we choose to perceive life and how perception is imposed on us by life itself. The movie raises questions about the authenticity of existence in any type of world and how environmental, social and biological restraint/constraint impacts on a person's sense of their subjective life.

And as always, Mamomru Oshii has tapped directly into the zeitgeist of our times.

Avalon sounds like a cross between The Matrix and World of Warcraft. It also sounds like it suffers from the bane of most Japanese anime -- heavy doses of angsty portent and symbolism borrowed/recycled from other anime or films (Mononoke Hime is a prominent exception to this deadening trend; I wrote briefly about this topic here: The String Cuts Deeper Than the Blade).

ReplyDeleteNice review. Thanks.

ReplyDelete