I often cringe when I’m asked how it is that I became involved in transhumanism. I’m loathe to admit that, as cliché as it sounds, the events of 9/11 played a major part in how my worldview was shaped in the first several years of the 21st century. Many key facets of my life, including my politics, spirituality, and interpersonal relationships, was impacted upon in one way or another by the events of that day.

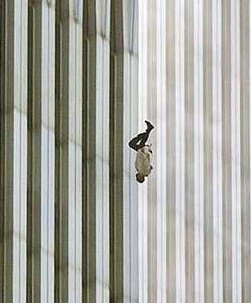

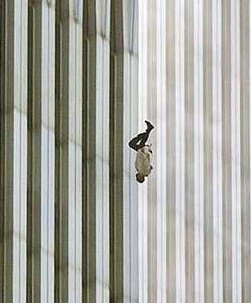

Watching desperate people throw themselves off the top of skyscrapers can have that effect. Those images in particular rattled me to the bone, cajoling me awake from the slumber I had found myself in. But because of my post 9/11 transformation, I am able to derive some positives from the horrid events of that day. In a very real way, the person I am today is much more aware, braver, self-assure and emotionally mature than that pre-9/11 version of me.

Trying to find positives in the aftermath of 9/11 is not an easy task. So many things have gone to the shits since that day. It has brought out the worst in so many. Since 9/11, the United States has launched a far reaching “war on terror” and an internal war on its own citizens where information is hidden and distorted and where covert surveillance and privacy breaches have quickly become the norm. The ‘new normal’ has further stratified an already divisive country; the United States is now truly a land of two cultures in which dialogue is becoming nearly impossible.

Another terribly regrettable side-effect of 9/11 has been the anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment that now characterizes a significant part of Western public opinion. The parallels to Maccarthism are striking. Today, the ‘communist threat’ has been replaced by the perceived ‘Muslim threat.’ Recently, while driving through the United States, I saw some disturbing signs of this ugliness. While at a truck-stop in Virginia I saw written on a toilet wall, “We hate sand-niggers.” Sure, I was in hillbilly heaven, but it reminded me of the hate and prejudice that still exists in the US and other countries. Arabs and Muslims have in no small way been the real victims of 9/11.

This alienation, along with the twisted inspiration that was imparted on some Muslims after 9/11, has resulted in the rise of groups and individuals more prone to radicalism. Recent events in the UK and Canada, in which young Muslim men were caught planning large-scale terrorist acts, indicate that home-grown terrorists may start to become an ongoing problem. I hope I’m wrong and that these are just spasmodic incidents in the wake of 9/11.

Things look bleak in the Middle East as well. The Taliban are giving coalition troops fits in Afghanistan, the US is concerned about full-scale civil war erupting in Iraq, and Israel is starting to show the strain of being surrounded by nations who would like nothing less than its destruction. And of course, there is the rise of Ahmadinejad in Iran and the ongoing theocratization of that country. More broadly, there is the spread of radical Islam among more moderate Muslims, poisoning what is normally a rather benign religion.

Yes, things have changed since 9/11 – that much is undeniable. Yet many of the geopolitical realities of today are part of broader trends, the roots of which extend back decades if not centuries. We are still dealing with the fallout caused by the end of the Cold War; a bipolar geopolitical arrangement is far more stable than a multipolar one. Nations are still coming to grips with the presence and proliferation of apocalyptic technologies. And then there is the insatiable demand for oil; the Middle East is unstable as it is because of its tactical significance as an energy provider. Exacerbating this, the inhabitants of the Middle East have reacted quite poorly to economic and cultural globalization (which they interpret as encroaching imperialism), a sentiment that has been fueled by the region’s deep commitment to religious values and institutions.

And it’s on the topic of religion that I’ll segue back to my own personal journey. I grew up in a Catholic neighborhood and went to Catholic schools. The language of religion is very familiar to me. Yet, despite my upbringing, I never really bought into religion. I was the perennial skeptic. When I was in my teens and early 20’s I was strictly atheist and a follower of scientific naturalism. Carl Sagan was my ultimate hero and guide.

But a funny thing happened to me on the way to my 30’s – I got married, had kids and somehow found myself going back to church. Sure, my wife at the time (we’re no longer together) influenced me to do so, but it felt like the right thing to do. After the first few awkward times attending church services I started to settle in. Soon thereafter my mind started to shut down. I passively accepted Christian metaphysics despite the cognitive dissonance it created in my mind. There was an undeniable cult-like quality to the whole thing. I started to basically sleepwalk through life, glued to television sitcoms and living unhealthily in both body and mind.

Thus, it was in this condition that I witnessed the events of September 11, 2001. On the morning of 9/11 I arrived at work and started my routine like any other day. My boss’s wife called and she was pretty much hysterical as she described to me how a plane had just hit the World Trade Centre.

Now, just to give you an indication of how messed up I was at the time, my first reaction was one of delight. Finally, I thought to myself, there’s something interesting going on in the world (looking back now, I understand how bored I was and how unfulfilling my life had become -- I was angry, frustrated and interpersonally disconnected). I then remembered how after WWII a small plane smashed into the Empire State Building. I thought it interesting that history had repeated itself in New York. I initially assumed that a small plane had hit one of the Twin Towers. The thought of terrorism never crossed my mind.

But then news soon came in that a second plane had hit the other tower and that both planes were commercial airliners. I froze in horror and immediately understood that a severe act of terrorism was underway. Then our office’s Internet connection pretty much went dead and we scrambled to find a radio. We spent the rest of the morning huddled around a radio trying to piece together the events that were quickly unfolding. I remember hearing that the towers had ‘collapsed’ but refused to fathom what that actually meant. It was as if some Hollywood movie had come to life.

When I got home that night I flicked on the news and saw the footage of what transpired that day. Massive explosions. People throwing themselves off the top of the Twin Towers. Scores dead. And then I saw with my eyes what my mind could not comprehend: the Towers collapsed into piles of dust taking thousands and thousands of people with them. It was all so terribly horrible and surreal.

Over the next few weeks and months I went into a deep depression, struggled with anxiety, and was thrust head-first into an existential crisis. There was one question in particular that I obsessively mulled over: Am I sufficiently prepared to deal with my own death? The answer was clearly no. I started to seriously question the complaceny with which I was treating my life. I started to feel a strong desire to engage with the world.

Rightly or wrongly, I started to blame my unhealthy attitude toward life and death on my church activities and on Christianity itself. I transferred that frustration to other religions and began to blame much of the world’s problems on religious extremism. In my mind, much of the fanaticism and nihilism of 9/11 was the result of religious fundamentalism. Today, my opinions haven't strayed too far from this, but my views have tempered over time.

At the same time, while I was drifting away from Christianity, I started to discover Eastern philosophies, particularly Buddhism. What was interesting was how Buddhism came to me. I kept discovering Buddhist references and ideas without explicity looking for it. It truly spoke to me and fit in perfectly with my atheist, scientific and moral frameworks. Soon after becoming a 'secular Buddhist' I started to develop a much healthier attitude about life and death. It was also during this time that my politics shifted decidedly to the left, I re-embraced humanism, and I rediscovered my love for cosmology and metaphysics. A lot had changed in these fields since the late 80’s and early 90’s and I had lots of catching up to do.

I was doing research on parallel universes in late 2001 when I came across

Nick Bostrom’s Website. That’s where I discovered this thing called ‘transhumanism.’ Bostrom's site immediately swept me up. It introduced me to a world in which such things as artificial superintelligence, uploading, molecular assembling nanotechnology, radical life extension and posthumanism were discussed in an academic context. The future was far more profound than I had ever imagined. Transhumanism also introduced me to the field of bioethics which has become a true passion of mine.

I spent the next year researching everything I could about transhumanism and came into contact with

James Hughes after reading his paper, “

The Politics of Transhumanism.” Soon afterwards, in August 2002, I met

Simon Smith and we co-founded the

Toronto Transhumanist Association and I became the deputy editor of

Betterhumans.

Simply put, I got my act together after 9/11. I discarded the detritus in my brain and went about the process of self improvement and rediscovery. My marriage did not survive these personal changes, but I feel that I’ve significantly improved as a person and I’m much better off. I became a vegetarian, took up yoga, started to meditate and lost some un-needed pounds. I now work out regularly and take vitamins and supplements. I am far more empathetic and personable with friends, and I am a far more patient, attentive and understanding father.

So, on this, the fifth anniversary of 9/11, I pause to reflect on all the changes that I've undergone in the past few years. 9/11 was not just an important milestone for world affairs, it also set me on a new course that has resulted in my life becoming so much more meaningful and fulfilling.

Shame that it took an event of such horror to turn things around for me.

My thoughts go out to everyone with similar stories to tell and for those who lost someone on September 11, 2001.

There are times when I feel my anti-religious views tend to the extreme, but then I'll read something by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and I suddenly get the feeling that I'm being downright reasonable. He often reminds me how my own opinions get tempered over time by dominating cultural norms, and how my anti-religious sensibilities are susceptible to the drift of cultural normalization.

There are times when I feel my anti-religious views tend to the extreme, but then I'll read something by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and I suddenly get the feeling that I'm being downright reasonable. He often reminds me how my own opinions get tempered over time by dominating cultural norms, and how my anti-religious sensibilities are susceptible to the drift of cultural normalization.